News ———— Memo

A map of the evident supercycle

In 50 years of unbacked paper money, central banks have proved that the one thing they are capable of, is in fact not to maintain the value of the currency, but to devalue it to almost nothing while keeping its users in the dark. The “no inflation”-lie, must still be one of the best magic tricks ever performed in modern history.

– From the memo Dawn of the supercycle from 2021

This observation from 2021 has proven prescient as we examine the current commodity supercycle. While it might look like inflation is contained at the moment, the rise in commodity prices is whispering about a near future of rising consumer prices.

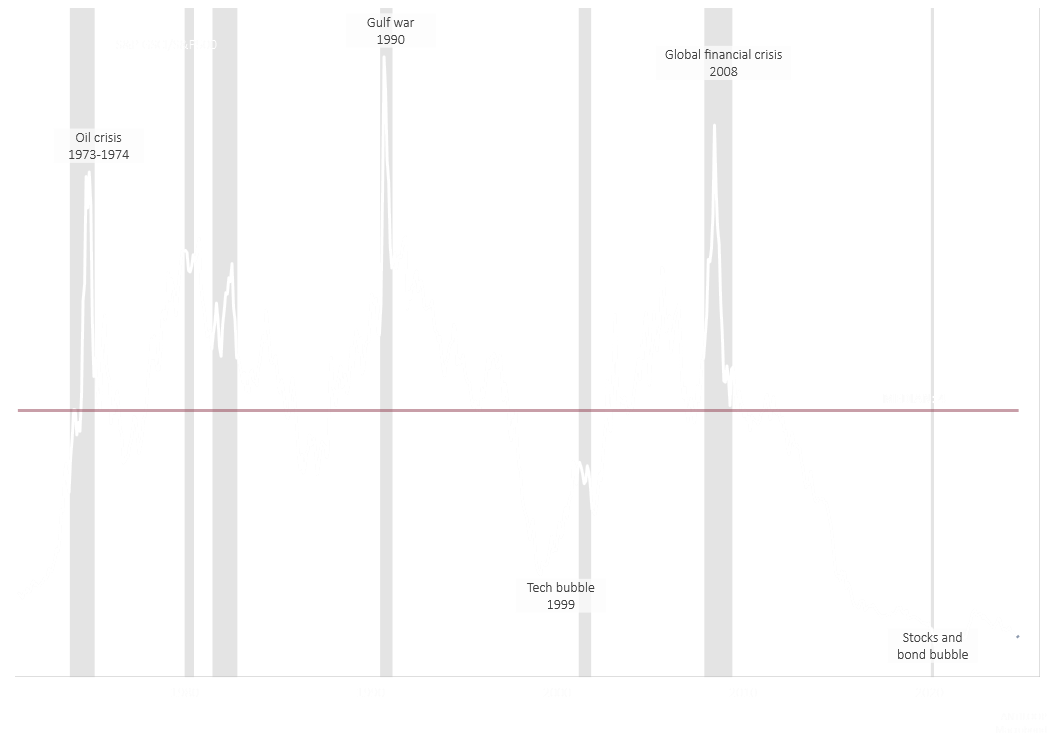

Most investors with a predilection to macro have seen the chart below more than once in the last few years. And believe me, I get it. It’s a great chart. It’s even partly responsible for my career and one of the reasons behind experimenting with building the first version of Antiloop’s TAA strategy, Cygnus. However, it only tells half the story.

Commodities have only been this cheap compared to stocks twice before, right before the 1970s commodities boom and during the 1999 tech bubble. Both times were followed by secular commodities bull markets.

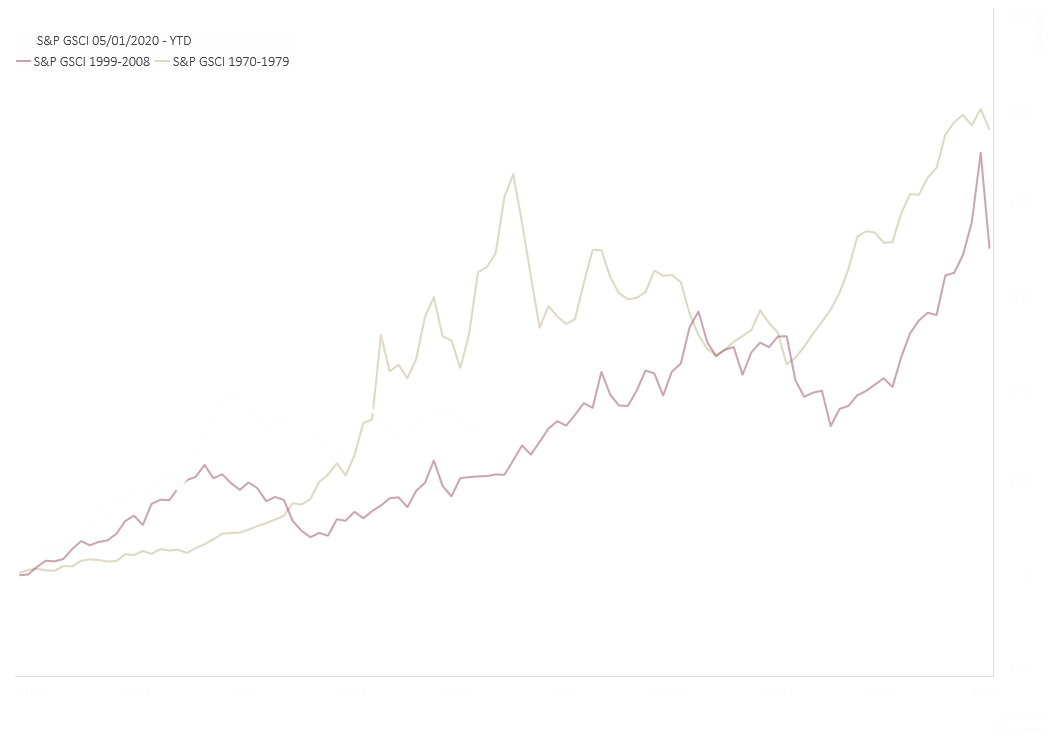

During both bull markets in the 1970s and the early 2000s, the price of commodities increased by around 500 percent over a decade before falling again. We believe that this cycle has already begun.

Since 2020, the broad commodities index S&P GSCI has returned almost 200 percent, and, when compared to the two previous supercycles, the current cycle follows the same pattern. While there are similarities, it is also essential to acknowledge that different driving factors characterize all three cycles. However, the most critical driving factor remains the same: easy monetary policy.

To understand why we believe this cycle has already begun, let's examine how previous supercycles unfolded.

A Tale of Three Eras: How Monetary Policy Shapes Commodity Cycles

Since the 1970s, the commodity market has witnessed three distinct supercycles, each shaped by unique economic and geopolitical factors.

The 1970-1979 supercycle was a perfect storm of economic upheavals. Oil shocks in 1973 and 1979 sent energy prices skyrocketing, causing widespread increases in consumer prices. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 led to currency devaluations, making commodities an attractive hedge against rising prices. Cold War tensions drove up prices of strategic resources, while rapid industrialization in developing economies sustained demand pressure. This combination created a decade-long commodities boom that reshaped global markets.

The 1999-2008 supercycle was primarily driven by China's voracious appetite for raw materials. China's massive infrastructure projects and rapid urbanization created unprecedented demand for commodities. Steel consumption skyrocketed, copper prices soared, and energy demand surged. This demand shock collided with underinvestment in commodity production from the previous two decades, creating supply constraints. A weak U.S. dollar made commodities more attractive to international buyers, while increased financialization of commodity markets amplified price moves.

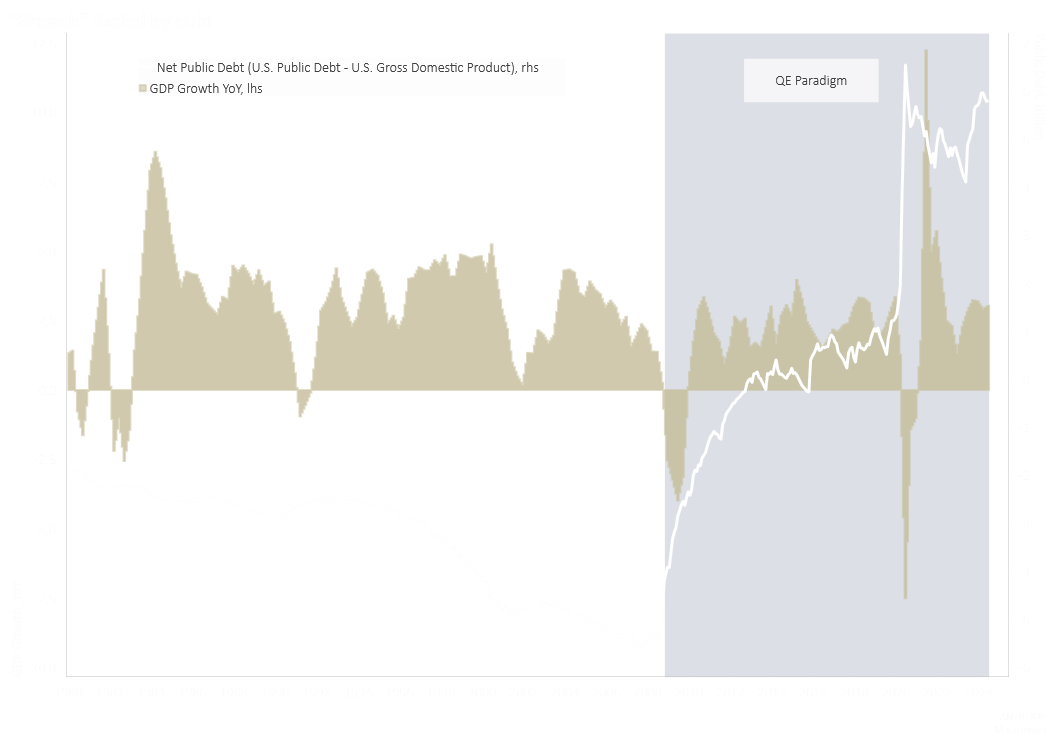

The current supercycle, beginning in 2020, is characterized by post-pandemic dynamics, a green energy revolution, and unprecedented monetary expansion. As economies recovered from COVID-19 lockdowns, pent-up demand collided with disrupted supply chains. Crucially, this cycle is underpinned by a significant monetary shift reminiscent of the 1970-1979 era. Since the introduction of quantitative easing in 2008, US public debt has grown to exceed the size of the economy by 2016, echoing the abandonment of the Bretton Woods system. This expansion of the monetary base, coupled with central banks' continued expansionary policies, has made commodities an attractive investment and hedge against rising consumer prices.

Is it different this time?

Yes and no. As mentioned above, the catalyst for this cycle was disrupted supply chains due to the COVID-19 lockdown. This could have led to short-term price fluctuations (noise) if it had not been for the actual signal: the aggressively expanded monetary base. Another difference is the additional driver coming from the attempts to limit global warming. We have covered the nuclear power renaissance previously here, and the memo is more relevant than ever.

The global energy crisis has fundamentally shifted the narrative around nuclear power. What was once viewed as a controversial energy source has become widely accepted as a crucial part of our energy future. Just a few weeks ago, Microsoft signed a deal to revive the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania. Last week, Amazon communicated that they had invested in developing SMRs through the nuclear start-up X-Energy, and Google said they had agreed to buy nuclear energy from SMRs developed by another start-up called Kairos Power.

While this nuclear renaissance could eventually lead to lower energy prices through reliable baseload power generation, the build-out will take decades. The immediate effect is quite the opposite – a massive increase in demand for uranium and other commodities needed for this unprecedented infrastructure expansion. And this is just one piece of the broader commodity-intensive green energy transition.

I did not intend to discuss nuclear power in this memo, although those who know me would tell you that I would never miss an opportunity to at least mention it if I had the chance.

Anyway, I'm not just spiraling away from the point. While the green energy transition makes this cycle unique, what makes it particularly intriguing is how multiple forces are converging. The push for decarbonization requires enormous amounts of raw materials at a time when years of monetary expansion has already set the stage for higher commodity prices. Meanwhile, geopolitical tensions are restricting access to critical resources.

When we look back at this period a decade from now, we might well view the green energy transition as the visible catalyst that everyone focused on, while the real driver – the great monetary experiment of the past 15 years – was hiding in plain sight. Like all great magic tricks, it was performed right in front of us, so obvious that we completely missed it. The greatest deception wasn't making money appear out of thin air, but making us forget what sound money looked like in the first place.